1. Introduction — Christianity Is Not One Argument Among Many. It Is the Foundation of All Reasoning

Most people approach Christianity as if it were simply one option on a shelf of competing belief systems. You compare it to atheism, Islam, Buddhism, or vague spirituality, weigh the arguments, and decide which one seems most persuasive. That way of thinking feels natural, fair-minded, and intellectually responsible. But it already assumes something massive before the conversation even begins: that there exists a neutral platform of reason from which all worldviews can be judged equally. The Transcendental Argument for God challenges that assumption at its root.

Christianity does not present itself merely as a set of religious claims competing for your vote. It presents itself as the truth about reality itself — including truth, logic, morality, meaning, and knowledge. In other words, Christianity is not just another argument within the system; it is a claim about the system itself. The God of Scripture is not offered as one explanation among many, but as the necessary precondition that makes explanation, argument, and intelligibility possible at all.

This is why the Transcendental Argument for God (TAG) feels different from most apologetic approaches. It does not begin by asking whether God exists as an isolated question. It asks something more basic and more unsettling: What must already be true for us to reason, argue, debate, and disagree in the first place? When that question is taken seriously, Christianity is no longer standing in line waiting to be evaluated. It is standing underneath everything else, holding the entire structure up.

1.1 There Is No Neutral Ground

One of the most persistent myths in modern thinking is the idea of neutrality — the belief that human beings can step outside of all assumptions, beliefs, and commitments and reason from a perfectly objective standpoint. We are told to “just follow the evidence,” “set faith aside,” or “reason without presuppositions.” But this ideal neutral ground exists nowhere outside of imagination. Every human being reasons from within a worldview, whether they admit it or not.

You don’t choose whether you have starting points; you only choose whether you acknowledge them. The atheist has them. The skeptic has them. The Christian has them. Even the claim “I don’t have presuppositions” is itself a presupposition. Everyone brings assumptions about logic, truth, morality, and the reliability of human reason to the table before a single argument is ever exchanged.

TAG presses directly on this uncomfortable reality. It exposes the fact that debates about God are never merely about evidence floating in midair. They are debates between entire worldviews — competing accounts of what reality is like and how we can know anything at all. The question is not whether you reason from faith commitments, but which faith commitments can actually support the act of reasoning you are already engaged in.

Once neutrality collapses, the discussion shifts dramatically. Christianity is no longer on trial before autonomous human reason. Instead, autonomous human reason itself is placed on trial. The issue becomes whether a worldview that excludes God can even justify the tools it relies on to make its case.

1.2 TAG: The Name, the Method, and the Difference

The word transcendental often intimidates people before the argument even begins. It sounds abstract, mystical, or hopelessly academic. But in philosophy, the term has a very specific and very practical meaning. A transcendental analysis asks not what exists, but what must already be true for something else to be possible. It looks beneath the surface of experience to identify its necessary preconditions.

Etymology Note: The word transcendental comes from the

Latin transcendere, meaning “to climb beyond.” In philosophy, it refers to that which stands above or prior to particular experiences — the conditions that make

experience possible in the first place.

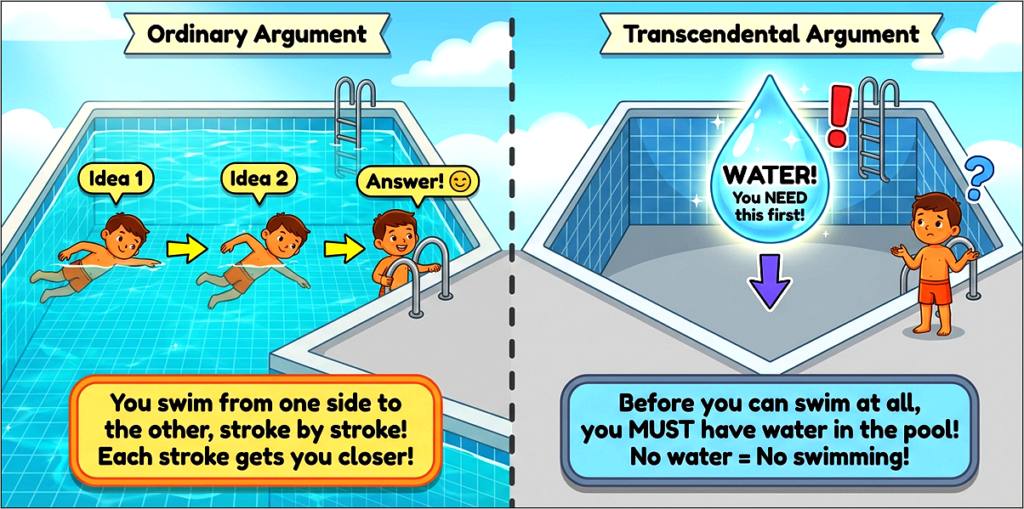

This is where TAG differs sharply from most “regular” arguments for God. A traditional argument might say, “Here is evidence X; therefore, God probably exists.” TAG works in the opposite direction. It begins with something we already take for granted — logic, morality, science, reasoning, communication — and asks what must be true for those things to make sense at all. Instead of moving from evidence to God, it moves from intelligibility to God.

| Ordinary Argument | Transcendental Argument |

|---|---|

| Moves toward a conclusion | Reveals a condition |

| Adds information | Exposes necessity |

| Can be rejected | Cannot be escaped |

| Probabilistic | Absolute |

Think of the difference like this: a standard argument tries to prove that a building exists by pointing at the bricks. A transcendental argument asks what must be in place for bricks to even function as a building. TAG is not primarily concerned with adding God to your worldview; it is concerned with exposing whether your worldview can stand without Him.

This is why TAG is often described as an argument about preconditions of intelligibility. It is not asking whether belief in God is comforting, useful, or culturally meaningful. It is asking whether reasoning itself — including the reasoning used to deny God — is even possible apart from the God revealed in Scripture. That is a fundamentally different question, and it requires a fundamentally different kind of argument.

1.3 Clearing Away the Confusion: What “Transcendental” Is — and Is Not

Before moving forward, it’s crucial to clear away several common misunderstandings that surround the word transcendental. TAG has nothing to do with Transcendental Meditation, New Age, mystical experiences, altered states of consciousness, or vague spiritual feelings. It is not about going beyond logic; it is about explaining why logic works in the first place. Nor does “transcendental” simply mean “transcendent.” While God is transcendent, the argument is not about reaching upward emotionally or intuitively. It is about identifying what must already be assumed whenever anyone thinks, reasons, or argues.

TAG is also not an appeal to subjectivity or psychology. It does not say, “You personally feel dependent on God, therefore God exists.” It says, “You are already operating within a framework of logic, morality, and meaning — and that framework requires an ultimate grounding that your worldview cannot supply on its own.” This is an objective challenge, not a personal one.

Finally, many people hear “transcendental” and immediately think “circular reasoning.” That concern is understandable, and it will be addressed directly later. But at this stage, it’s enough to say this: every ultimate authority must, at some level, account for itself. The question is not whether there is circularity, but whether the circle is vicious or virtuous — whether it collapses into arbitrariness or successfully grounds the very reasoning used to examine it.

Once these confusions are removed, the argument can finally be heard for what it is. TAG is not mystical, evasive, or anti-rational. It is an unapologetically rigorous claim that Christianity alone provides the necessary foundation for the very tools we all use to make sense of the world. With that clarified, we are ready to ask the next and unavoidable question: Can any non-Christian worldview actually account for the preconditions of intelligibility it relies on every day?

2. The Unbeliever’s Worldview Cannot Account for the Preconditions of Intelligibility

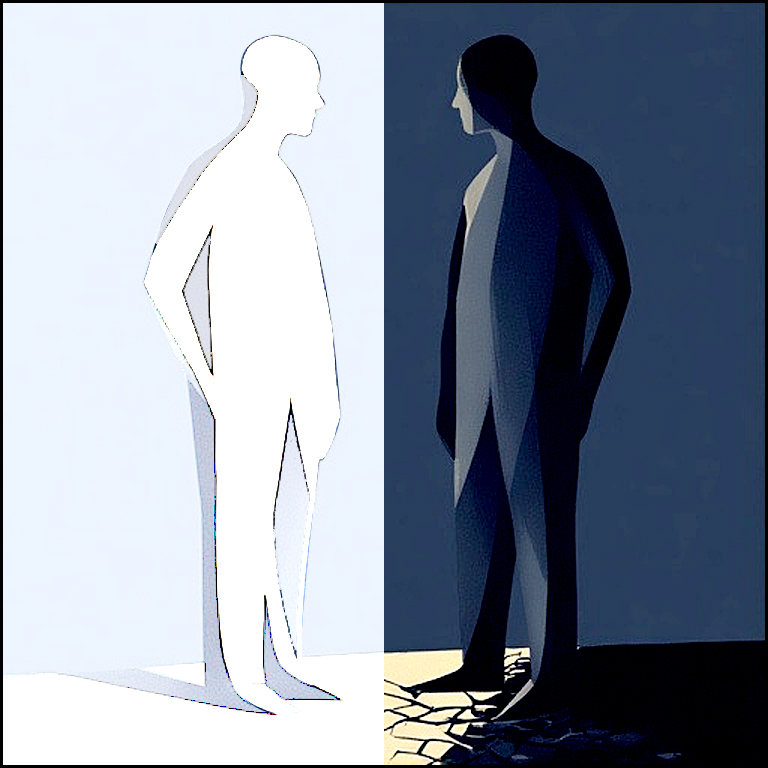

Every worldview makes promises. Some promise freedom. Some promise progress. Some promise neutrality. But the real test of a worldview isn’t how confident it sounds — it’s whether it can explain the very tools it uses to make its case.

The Transcendental Argument doesn’t begin by asking, “Does God exist?” It begins by asking something far more basic: “How is knowledge possible at all?” How do logic, meaning, moral obligation, and scientific reasoning even get off the ground? What must already be true for discussion, debate, and disagreement to make sense?

This is where the unbeliever’s worldview quietly stumbles. Not because unbelievers can’t reason — they reason constantly — but because their worldview cannot account for the reasoning they depend on. They borrow tools they cannot justify. They live as though the world is ordered, meaningful, and knowable, while explaining it as though it is ultimately the product of chance, matter, and motion.

TAG presses this tension without insult or theatrics. It simply asks whether a worldview can explain its own success. And when pressed honestly, non-Christian worldviews consistently collapse into borrowed capital — relying on Christian assumptions while denying the Christian foundation.

“Everyone who hears these words of Mine and does them will be like a wise man who built his house on the rock.”

(Matthew 7:24–25)

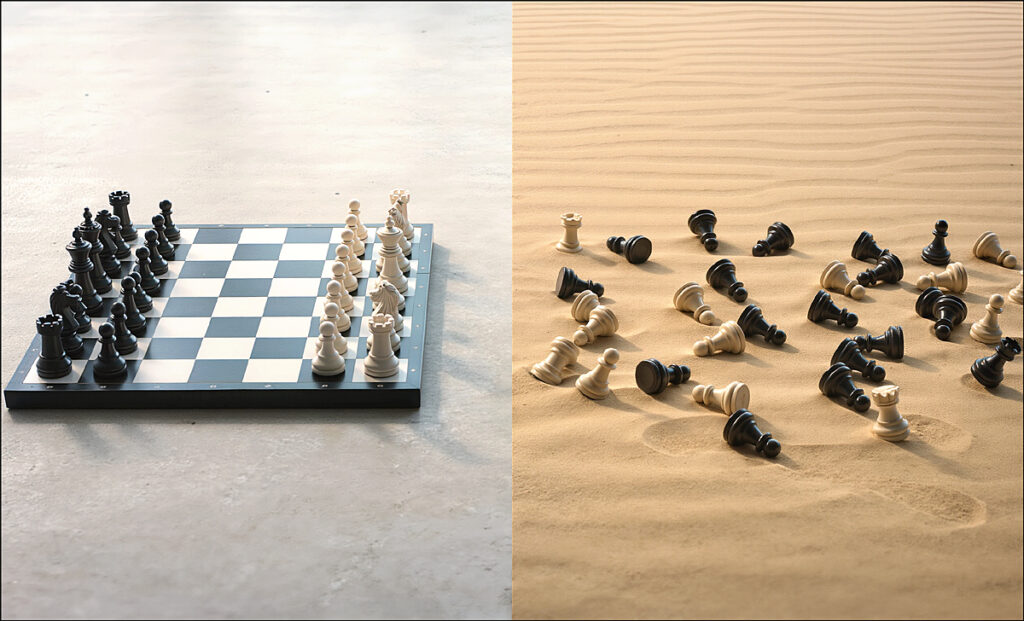

2.1 The Chessboard and the Sand — Why Rules Reveal the Necessity of a Designer

Imagine walking up to two scenes.

In the first, you see a chessboard laid out perfectly. The pieces are arranged with intention. You instantly recognize that the board operates according to rules — not rules you invented, but rules that govern the game. Even if you’ve never played chess, you know one thing immediately: this system didn’t organize itself. It reflects design, purpose, and structure.

Now picture the second scene. A stretch of sand on a beach. Grains scattered randomly. No boundaries. No governing principles. No expectations. You don’t ask what the sand “means” or what move comes next. You don’t argue with it. You don’t learn from it. It simply is.

Here’s the question TAG forces us to face: Which of these does reality resemble?

We reason as though the universe is a chessboard — structured, intelligible, governed by consistent rules. We expect logic to apply tomorrow the same way it did today. We expect causes to lead to effects. We expect words to carry meaning and arguments to follow patterns. But if reality is ultimately like sand — the result of blind, purposeless processes — then those expectations are illusions.

This is not a minor philosophical quibble. It strikes at the heart of everyday life. When students study for exams, when scientists run experiments, when judges weigh evidence, when activists appeal to justice — all of them assume the world is ordered and knowable. They assume the rules are real and binding.

But rules don’t float in midair. Games require rule-givers. Systems require structure. Meaning requires mind.

Christianity does not merely assert that the world is like a chessboard. It explains why it is. A rational God created a rational world and rational creatures to understand it. Order is not imposed by human thought; it is discovered because it was already there.

You can’t play a rule-governed game in a universe made of sand.

The power of this illustration is its simplicity. You don’t need a philosophy degree to feel its force. You already live as though the world is intelligible. TAG simply asks whether your worldview can explain why.

And once that question is asked honestly, the debate has already begun.

3. Logic — Why the Laws of Thought Require the God of Scripture

Every argument assumes logic before it ever proves anything.

Before someone can deny God, they must assume that their denial makes sense. Before anyone can reason, question, object, or even doubt, they rely on unchanging laws of thought — identity, non-contradiction, and rational inference. These are not discovered in a lab. They are not voted into existence. They do not evolve. They simply are, and they bind every mind equally.

That fact alone raises a serious question: what kind of universe makes rational thought possible at all?

Logic is universal, immaterial, invariant, and authoritative. It applies everywhere, at all times, to all people — regardless of what anyone believes about it. But here is the tension TAG presses relentlessly: a universe of matter, motion, and chance has no room for such things. Atoms don’t obey logical laws; minds do. Chemical reactions don’t recognize contradictions; thinkers do.

Christianity does not try to reduce logic to matter. It grounds logic in God Himself — eternal, rational, self-consistent, and unchanging. Logic reflects His thinking, not human invention. That is why logic binds all people, including those who deny Him.

And this is where autonomy begins to crack.

3.1 The Myth of Autonomous Reasoning — The Egocentric Predicament

The egocentric predicament is deceptively simple: if human reason is the ultimate authority, then each individual becomes the final judge of reality.

Autonomy promises objectivity, but it delivers isolation.

When someone claims to reason “independently” of God, they are not escaping presuppositions — they are enthroning themselves. Their mind becomes the court of final appeal. Their reasoning is validated by their reasoning. And this is where transcendental arguments outside of Christianity collapse. They may appeal to logic, meaning, or knowledge, but they cannot escape the fact that their foundation is still the human mind.

This is why many so-called transcendental arguments sound impressive but go nowhere. They identify a necessary feature of knowledge but fail to ground it beyond the thinker. They place a single stone — a clever insight — into what Van Til (A Dutch-American Reformed theologian) famously described as a bottomless ocean. A lone argument, detached from a worldview, cannot carry the weight of knowledge itself.

Young adults encounter this constantly, even if they don’t recognize it by name. Everyone claims to value logic, but no one agrees on why it binds us. Everyone wants rational debate, but everyone reserves the right to redefine reason when it becomes inconvenient. Autonomy pretends to offer neutrality, but in practice it produces a thousand private rationalities.

TAG exposes this gently but decisively: unless logic is grounded in something greater than human minds, it has no authority over them.

The egocentric predicament shows why non-Christian transcendental arguments fail — not because they notice nothing true, but because they stop short of the only foundation that can support what they observe.

Autonomy does not eliminate authority.

It merely relocates it into the self.

3.2 The Aim of Presuppositional Apologetics — Faithfulness, Not Autonomy

Presuppositional apologetics does not aim to prove God by pretending to stand above Him. It refuses to play that game altogether.

The goal is not intellectual independence but faithfulness: thinking God’s thoughts after Him, not replacing them with our own. This does not weaken reason; it secures it. When logic is grounded in the God who created and governs all things, reasoning finally has a home. Knowledge becomes possible. Meaning becomes coherent.

Did you know? Rodin’s The Thinker was originally conceived as Dante Alighieri, reflecting on The Divine Comedy—a meditation on heaven, hell, judgment, and the moral order of reality. Even our most familiar symbols of ‘pure reason’ already presuppose God, because without Him the very thinking the image depicts could not exist, let alone make sense.

This approach is profoundly freeing for the believer. You do not need to apologize for your starting point. Everyone has one. Christianity simply acknowledges it openly and shows that only its foundation can support the weight of rational life itself.

For the college student navigating classrooms full of competing truth claims, this is a relief. You are not irrational for trusting Scripture. You are not anti-intellectual for rejecting autonomy. You are standing on the only ground that makes thinking possible at all.

Presuppositional apologetics does not ask the unbeliever to stop reasoning. It asks them to recognize what they already rely on every time they reason — and to follow that reliance where it actually leads. And where it leads is not inward, but upward.

You haven’t got the power to change a sinner’s

Greg Bahnsen — The Aim of Apologetics Series

heart, but you do have the ability to shut the sinner’s mouth.

This is why presuppositional apologetics does not claim to convert anyone by argument alone. As Dr. Greg Bahnsen (American Calvinist philosopher and Christian apologist) famously said, “You haven’t got the power to change a sinner’s heart, but you do have the ability to shut the sinner’s mouth.” The goal is not rhetorical victory, but faithful obedience: “always being prepared to make a defense” (1 Peter 3:15) and “silencing those who contradict” (Titus 1:10–16). When a worldview collapses under its own weight, the debate ends rationally—even if it continues socially. The chess pieces may still be in the sand, but the game itself has been exposed as impossible.

4. Morality — Why Objective Moral Obligations Require a Holy Lawgiver

There are moments in life when moral neutrality evaporates instantly.

A child abused.

A genocide denied.

A woman assaulted.

A man betrayed by those he trusted most.

In those moments, no one says, “Well, that’s just your perspective.” No one shrugs and says, “Morality is relative.” We don’t merely dislike such acts — we condemn them. We speak as if a real standard has been violated, as if someone is genuinely guilty, as if justice is owed.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky understood this deeply. In The Brothers Karamazov, Ivan famously wrestles with the problem of evil — not as a philosopher, but as a human being who cannot stomach a world where children suffer unjustly. His outrage is visceral. He does not argue calmly; he protests. And that protest reveals something crucial: moral outrage assumes moral reality.

You cannot meaningfully protest evil if evil is only a chemical reaction or a social preference.

Young adults feel this tension constantly. We demand justice on social media. We cry out against oppression. We insist on human dignity, rights, and accountability. But here is the uncomfortable question TAG refuses to let us dodge:

Where do those moral “oughts” come from?

If the universe is the product of time, chance, and matter, then morality is ultimately a human invention. Preferences evolve. Cultures change. Power decides. In such a world, “wrong” can only ever mean “I don’t like this” or “we voted against it.”

But that is not how we live.

We live as if some actions are truly wrong — even if everyone applauds them. We live as if some things are really good — even if they cost us everything. TAG points out the tension: objective moral obligations make no sense in a godless universe, yet we all rely on them constantly.

Christianity alone explains this lived reality. Moral law exists because a moral Lawgiver exists. Good is not arbitrary; it is rooted in God’s holy character. Evil is not merely inconvenient; it is rebellion against that standard. Justice is not a social construct; it is grounded in who God is.

This is why moral arguments cut so deeply. They touch what we already know but often suppress: that we are accountable creatures in a moral universe.

We do not just feel moral outrage.

We assume the universe agrees with us.

4.1 Exposing Internal Inconsistency: The Presuppositional Method in Action

This is where presuppositional apologetics does its most devastating — and clarifying — work.

When someone says, “There is no God, but some things are objectively wrong,” TAG does not mock them. It simply asks them to explain how those two claims coexist. What grounds moral obligation in a universe with no moral authority? Why should anyone obey a standard that ultimately comes from nowhere?

Most people can’t answer — because they’re living on borrowed capital.

They reject God intellectually but cling to His moral furniture. They demand justice while denying the Judge. They cry out for accountability while rejecting the Lawgiver. Presuppositional apologetics exposes this inconsistency gently but firmly, not to win arguments, but to reveal truth.

This is why ethics is such a powerful doorway for real conversations. You don’t need abstract philosophy. You can ask real questions about real life: Why do you think that’s wrong? Why should anyone be held accountable? Why does injustice bother you so deeply?

TAG does not need to invent morality; it simply shows that only Christianity can make sense of the morality everyone already assumes.

For the young adult navigating a world full of outrage, activism, and moral claims, this matters immensely. It means your instincts about justice are not illusions. They are echoes. They point beyond you, beyond culture, beyond consensus — to a holy God who has written His law on the human heart.

And once that realization lands, morality is no longer a debate topic. It becomes a summons.

5. Science and Induction — Why the Uniformity of Nature Presupposes God

Modern people trust science instinctively. We wake up expecting gravity to work, electricity to flow, phones to connect, and medicine to behave tomorrow the way it did yesterday. We don’t wake up wondering whether water will suddenly start freezing at room temperature or whether the laws of physics will randomly change before lunch. Life would be impossible if we did.

But here’s the uncomfortable question most people never stop to ask: why do we expect the world to be orderly at all?

Science does not merely observe facts; it depends on patterns. Experiments assume repeatability. Conclusions assume consistency. Predictions assume that the future will resemble the past in relevant ways. This assumption — that nature is uniform — is not something science can prove by experiment, because every experiment already assumes it.

This is what philosophers call induction: reasoning from past experience to future expectation. We do it constantly, instinctively, and necessarily. But the deeper question remains unanswered in unbelieving worldviews: what justifies that confidence?

From a purely naturalistic standpoint, there is no reason the universe must behave consistently. Atoms do not carry moral obligations to repeat themselves. Chance does not promise tomorrow will resemble today. And yet, every scientist — whether atheist or Christian — lives as if the universe is intelligible, predictable, and governed by stable laws.

TAG presses the issue: what makes that assumption reasonable?

Christianity alone provides a satisfying answer. The world is orderly because it is created and sustained by a faithful, rational, personal God. The laws of nature are not brute facts; they are expressions of God’s ongoing providence. The reason experiments work is not because the universe is lucky, but because God is consistent.

This is not anti-science. It is the very foundation of science. Historically, it was precisely this biblical view of creation that gave rise to modern scientific inquiry. The universe could be studied because it was believed to be intelligible — and intelligible because it reflected the mind of its Creator.

Science works because the world is dependable,

and the world is dependable because God is faithful.

For the young adult navigating STEM fields, medicine, engineering, or tech, this matters deeply. Every lab report, algorithm, and data model quietly assumes that reality will cooperate tomorrow the way it did yesterday. TAG simply asks the question others avoid: why should it?

5.1 The Impossibility of the Contrary

This is where the Transcendental Argument tightens its grip.

TAG does not merely say that Christianity explains science better than unbelief. It says something far stronger: without the Christian worldview, science itself becomes unintelligible.

Imagine a universe governed only by time, chance, and matter. In such a world, there is no guarantee of order — only temporary regularities we hope will continue. Any expectation of uniformity becomes a psychological habit, not a rational certainty. Science becomes an act of faith with no object worthy of trust.

This is not an abstract point. It is deeply personal. It means that the God Christians proclaim is not distant from daily life. He is the reason the world holds together at all. The ground beneath your feet, the order in your studies, the predictability you rely on — all of it already testifies to Him.

Yet unbelievers live as if the world is stable. They run experiments. They build technology. They stake lives on medical predictions. They trust tomorrow. TAG exposes the tension: they borrow from the Christian worldview while denying its source.

This is what Van Til and Bahnsen called the impossibility of the contrary. It means that when you remove the God of Scripture, the very things needed to argue against Him — logic, evidence, consistency, prediction — collapse.

Christianity does not merely fit science. It makes science possible. It alone can account for a universe that is rational, reliable, and open to investigation. Every time someone performs an experiment expecting consistent results, they are unknowingly acting in line with the biblical worldview.

And once this clicks, the conversation changes. Science is no longer a threat to faith. It becomes a witness.

6. Answering Common Objections to the Transcendental Argument

Whenever the Transcendental Argument is presented clearly, objections usually arrive quickly — not because the argument is weak, but because it presses too close to the foundations people assume without thinking about them. TAG does not merely challenge conclusions; it challenges starting points. And when someone’s intellectual ground is being questioned, the response is often emotional before it is rational.

This section is not about scoring debate points. It is about helping readers recognize why certain objections feel compelling at first — and why, upon closer inspection, they fail to touch the heart of the argument. Most objections to TAG are not new. They have been raised, answered, and clarified repeatedly, especially in the work of Van Til and Bahnsen. But more importantly, they are addressed by Scripture itself, which never apologizes for beginning with God.

The most common objection — by far — is the charge of circular reasoning.

6.1 “That’s Circular Reasoning”

At some point in almost every TAG conversation, someone will lean back and say it: “That just sounds circular.” And on the surface, the criticism can feel decisive — especially to young adults who have been trained to think that “circular” automatically means “irrational.”

But here’s the first thing that needs to be said plainly: all ultimate worldviews are circular at the foundation level. There is no escaping this. The question is not whether a worldview is circular, but whether its circle is large enough to account for reality.

When someone appeals to logic to disprove God, they are already assuming logic works. When they appeal to science, they are assuming the uniformity of nature. When they appeal to morality, they are assuming objective moral categories. None of those assumptions can be proven without presupposing them. That is not a Christian problem — it is a human one.

What TAG does differently is refuse to hide that circularity. It brings it into the open and asks the harder question: Which starting point can actually justify the tools we all use every day?

Christianity openly reasons from God because God is not a conclusion reached by reasoning — He is the precondition that makes reasoning possible. To demand that God be proven without assuming Him first is like demanding that eyesight be proven without using sight. The request misunderstands the category.

This is why Bahnsen famously responded that Christianity’s “circularity” is virtuous, not vicious. It is the kind of circularity that exists when an ultimate authority must authenticate itself. God cannot appeal to something higher than Himself, because nothing higher exists. When God speaks, He speaks with self-attesting authority — and Scripture is unapologetic about this.

What makes this powerful — and devastating to unbelieving worldviews — is that they cannot escape circularity either, but their circles collapse under pressure. They assume logic without grounding it. They assume morality without justifying it. They assume meaning while denying any ultimate source of meaning. TAG exposes this inconsistency and presses the unbeliever to live up to their own claims.

For the Christian reader, this realization is freeing. You do not need to pretend neutrality. You do not need to apologize for starting with Christ. Jesus Himself did not. He spoke as One who was the truth, not as someone hoping His claims might pass independent inspection.

The issue is not circular reasoning.

It is whether your circle can hold reality together.

When someone says, “That’s circular,” what they often mean is, “I don’t like that your starting point is explicit.” TAG gently but firmly replies: Neither is yours neutral. The difference is that Christianity can account for the very standards being used to object.

And this is where the argument turns evangelistic. The charge of circularity is not a dead end — it is an invitation. It opens the door to show that only the Christian worldview can make sense of the reasoning process both parties are already using. Not by winning a technical debate, but by revealing that Christ has been the ground beneath the conversation all along.

7. The Transcendental Argument Is Biblical, Not Philosophical Speculation

One of the most common misunderstandings about the Transcendental Argument is the belief that it is a clever philosophical invention later “added” to Christianity. That assumption collapses the moment Scripture is allowed to speak for itself. TAG is not a foreign framework imposed on the Bible; it is a way of describing what the Bible already does. Long before philosophers debated transcendental reasoning, Scripture presented God as the necessary precondition for truth, knowledge, morality, and meaning.

This is precisely what Cornelius Van Til saw and what Greg Bahnsen relentlessly emphasized: Christianity does not argue toward God as a conclusion; it reasons from God as the starting point. That is not philosophical arrogance. It is biblical faithfulness. The God of Scripture does not compete for plausibility among other explanations. He declares Himself as the One “in whom we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). Remove Him, and nothing else makes sense — including the act of arguing against Him. This is not a generic theism, but the God who has revealed Himself as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: personal, eternal, and self-consistent in His being.

The Bible never treats God as a hypothesis. It treats Him as the necessary reality without which no fact, no thought, and no moral judgment could exist. TAG simply names this reality and presses it into conscious clarity.

TAG does not import philosophy into Scripture; it exposes the foundations of reason and meaning Scripture already embodies.

7.1 Jesus Christ as the Logos — The Personal Ground of Truth, Logic, and Meaning

The heartbeat of the Transcendental Argument is not an abstract principle — it is a Person. Scripture identifies Jesus Christ as the Logos, the eternal Word through whom all things were made and by whom all things hold together (John 1:1–3; Colossians 1:16–17). This is not poetic imagery. It is a metaphysical claim. Logic, order, meaning, and intelligibility are not floating abstractions. They are grounded in Christ Himself.

Grounded in Christ, the Logos:

— Van Til, Why I Believe in God

God is the All-Conditioner, the condition behind everything, the One Who makes all things the way they are.

John does not say that Jesus uses logic or teaches wisdom. He says Jesus is the Word — the eternal self-expression of God, eternally with the Father and Himself God (John 1:1). Colossians 2:2–4 presses this even further: “in whom are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge.” Not some wisdom. Not religious wisdom alone. All wisdom and knowledge. That is a transcendental claim. This only makes sense if Christ shares fully in the divine nature, for only God can be the ultimate ground of all wisdom and knowledge. It means that every true thought, every valid inference, and every meaningful distinction already depends on Christ, whether acknowledged or not.

This is why Jesus does not argue like a philosopher seeking common ground. He speaks with authority because He is the ground. When He declares, “I am the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6), He is not offering a religious option. He is identifying Himself as the necessary condition for knowing anything at all. Truth is not something external to Him. It exists because of Him.

Van Til recognized that this biblical teaching leaves no room for autonomous reasoning. Bahnsen sharpened the point: if Christ is the Logos, then all reasoning already borrows from Him. Logic works because Christ is faithful. And because the Father, Son, and Spirit are eternally consistent with one another, the universe Christ sustains is intelligible rather than chaotic. Meaning exists because Christ is coherent. Knowledge is possible because the world and our minds are created and sustained by the same Lord.

Logic, meaning, and knowledge are not

abstract; they are personal because their source is personal.

7.2 Jesus Is Already Arguing Transcendentally

Once you see this, Jesus’ teaching takes on a new clarity. He does not invite neutral evaluation. He exposes foundations. When the rich young ruler calls Him “good,” Jesus responds, “Why do you call Me good? No one is good except God alone” (Mark 10:18). This is not deflection — it is a moral transcendental move. Jesus is identifying God as the precondition for moral categories. You cannot meaningfully speak of goodness while detaching it from the Triune God who defines, embodies, and judges goodness.

The same structure appears throughout Jesus’ ministry. In John 8:24, He declares, “Unless you believe that I am, you will die in your sins.” That is not merely a warning. It is a claim about reality itself. Without Christ, sin cannot even be properly understood, let alone resolved. In John 6:55, Jesus grounds what is truly real — life, sustenance, salvation — in Himself. He defines metaphysical reality, not by argument alone, but by identity.

And when Jesus says, “You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free” (John 8:32), He is not presenting a method detached from Himself. Just verses later, He identifies Himself as that truth. Obedience to His words is the pathway to knowledge because He is the epistemological foundation. Knowing is not autonomous discovery; it is covenantal submission to the Triune God who speaks.

Jesus’ parable of the wise and foolish builders (Matthew 7:24–27) brings this into sharp focus. He does not compare two equally plausible foundations. He contrasts a foundation with no foundation at all. One stands under pressure. The other collapses. That is transcendental reasoning in narrative form. Jesus is showing that without Him, life and thought do not merely fail morally. They fail structurally.

Scripture Already Models TAG

The apostles follow this same pattern. In Acts 17, Paul stands before the philosophers at the Areopagus — a culture saturated in ideas, debate, and speculation. He does not flatter their neutrality. He confronts their foundations. He begins with God as Creator, Sustainer, and Judge, declaring that God is not far from anyone because all people already depend on Him (Acts 17:22–31). The same God Paul proclaims is the God revealed in Christ, now commanding all people everywhere to repent. Paul’s argument is unmistakably transcendental: God is the condition for life, breath, reason, and accountability.

Earlier in Acts 17:2–3, Paul reasons from the Scriptures, not because he rejects logic, but because Scripture is his starting authority. Reason is his tool — grounded in God, shaped by Christ, and exercised covenantally. This is exactly what Bahnsen emphasized: Christian reasoning is not less rational; it is the only reasoning that can justify rationality itself.

Paul did not argue to Scripture; he argued

from it, because reality already stands on God’s Word.

Seen this way, TAG is not an innovation. It is recognition. Van Til did not invent a new apologetic method. Bahnsen did not manufacture a clever strategy. They simply gave names and structure to what Scripture has always done: expose false foundations and proclaim Christ as the necessary ground of all intelligibility.

Once this clicks, the Transcendental Argument stops feeling complicated and starts feeling obvious. It becomes prima facie biblical. Christianity is not one explanation among many. It is the context in which explanations are even possible because Jesus Christ, the eternal Son of the Father, revealed and proclaimed by the Spirit — is Lord of truth, logic, meaning, morality, and knowledge itself.

8. TAG and Evangelism — Why This Matters in the Real World

If the Transcendental Argument stopped at intellectual coherence, it would be interesting but incomplete. Bahnsen is adamant that TAG exists for a much larger purpose: obedient discipleship. Jesus did not command His followers to win debates, accumulate philosophical trophies, or merely feel confident in private belief. He commanded them to make disciples of all nations — students who think, reason, live, and submit to Him as Lord. TAG is not a detour from that mission. It is one of its sharpest tools.

This is where presuppositional apologetics collides with real life. Every conversation about God, truth, justice, science, or meaning is already a discipleship moment — whether we recognize it or not. People are constantly teaching others how to think, what counts as knowledge, and what deserves ultimate loyalty. Bahnsen’s point is unsettling but liberating: no one is neutral, and no conversation is spiritually empty. The question is not whether discipleship is happening, but whose worldview is discipling whom.

Every argument is already an act of discipleship,

either toward Christ or in rebellion against Him.

For many young Christians, evangelism feels paralyzing because it’s framed incorrectly. We’re taught to think we must first master every objection, gather airtight evidence, and somehow meet unbelievers on “neutral ground.” TAG shatters that illusion. Jesus never invited neutrality (Matt12:30). He exposed foundations. When He spoke of houses built on rock or sand, He wasn’t offering lifestyle advice — He was revealing a transcendental divide. One foundation stands. The other collapses. There is no third option.

Bahnsen presses this same strategy into evangelism. TAG teaches us to stop granting unbelief the moral and intellectual high ground. When someone argues, doubts, critiques, or demands justification, they are already relying on God’s world, God’s logic, and God’s moral order. Evangelism, then, is not begging someone to add God to their worldview — it is calling them to repentance for borrowing from Him while denying Him.

This is why TAG is not aggressive, arrogant, or manipulative. It is honest. It takes people seriously as image-bearers who already know God but suppress that knowledge (Romans Chapter 1). It also takes Jesus seriously as Lord, not merely as a topic of discussion. When Christians learn this method, they stop treating faith as fragile and start treating Christ as authoritative — over reason, over meaning, and over every conversation.

And this is where the call to action becomes unavoidable. If you are a disciple of Jesus, you are not merely allowed to learn this method — you are responsible to. The Great Commission is not fulfilled by sincerity alone. Jesus commands teaching — teaching people to observe everything He commanded. That includes how He reasons, how He exposes false foundations, and how He calls people out of intellectual rebellion and into truth.

Jesus does not ask permission to be relevant.

He is the condition that makes relevance possible.

TAG equips believers to walk into classrooms, workplaces, coffee shops, and online spaces without fear. It teaches you how to listen carefully, identify presuppositions, and gently but firmly press the deeper question: What makes your thinking possible at all? It shifts evangelism from surface-level persuasion to foundational confrontation — not to win arguments, but to summon people to the only worldview that can sustain life, thought, and hope.

This is not optional training for elite thinkers. It is discipleship for faithful Christians. To refuse to learn it is not humility — it is surrendering the ground Jesus already owns. The nations are being discipled every day by secularism, skepticism, and autonomy. Christ’s followers are commanded to respond, not with borrowed tools, but with the truth that every fact already belongs to Him.

9. Conclusion — Every Fact Already Testifies to the God We Proclaim

By the time Bahnsen brings the lecture series to a close, one thing should be unmistakably clear: the Transcendental Argument is not about adding God to a worldview that otherwise works fine. It is about exposing the reality that nothing works at all unless God is already there. Every time we reason, argue, judge right and wrong, or expect the world to behave consistently, we are standing on assumptions that only make sense if the Christian God is real. God is not the conclusion of a long chain of reasoning; He is the ground beneath it.

This is why TAG feels different from most apologetic arguments. It doesn’t start by asking, “What evidence would convince you?” It starts by asking something more uncomfortable: What are you already relying on in order to ask that question? When someone demands proof, argues logically, or appeals to fairness or science, they are already using tools that presuppose order, meaning, and truth. Bahnsen’s point is that these tools do not float in midair. They require a foundation. And that foundation is the God of Scripture.

God is not discovered at the end of reasoning.

He is the reason reasoning works at all.

For young adults especially, this cuts against the grain of how we’re taught to think. We’re told that facts are neutral, that beliefs are private, and that everyone simply interprets the same raw data differently. TAG dismantles that idea. There are no “brute facts.” Every fact is already interpreted within a worldview. Every interpretation already assumes something about reality, knowledge, and truth. The real question is not whether you have presuppositions — it’s whether your presuppositions can actually support the weight you put on them.

Bahnsen presses this point relentlessly: unbelief is not merely mistaken; it is internally unstable. The skeptic depends on logic while denying its source. The moral critic condemns injustice while rejecting any ultimate standard of justice. The scientist trusts the future to resemble the past while denying any reason the universe should behave consistently. These are not minor inconsistencies — they are cracks at the foundation. TAG shows that when pressure is applied, non-Christian worldviews collapse under their own assumptions.

The Christian worldview, by contrast, does not borrow its tools from elsewhere. It begins with the self-revealing God who created the world, governs it consistently, and made human beings in His image to know it. Logic reflects His thinking. Moral obligations reflect His character. Scientific regularity reflects His faithful providence. On this foundation, facts can be facts, arguments can be arguments, and meaning can be meaning.

There are no neutral facts waiting to be interpreted.

Every person encounters God’s world already loaded with

meaning—even when they deny the God who gives it.

This is why Bahnsen insists that TAG does not merely defend Christianity; it exposes Christianity as unavoidable. Even the act of denying God requires standing on ground that only God provides. Whether one acknowledges it or not, every argument, every judgment, and every experience already testifies to the God we proclaim. The task of apologetics is not to invent that testimony — it is to make it impossible to ignore.

Epilogue. Next Step — Why You Must Listen to the Full Lecture Series

This article has argued that TAG exposes Christianity as unavoidable and that apologetics makes the world’s existing testimony impossible to ignore. Dr. Greg Bahnsen’s Transcendental Argument Lecture Series is presented here as the next step for the reader who wants to see that exposure developed in cumulative detail. The lectures unfold progressively, layering historical context, philosophical engagement, and presuppositional insight, building toward a robust understanding of why Christianity alone provides the conditions for intelligibility. Engaging the full series allows the student to do in reality what The Thinker portrays in bronze: reflecting within a world already illuminated by God rather than inventing light for himself.

Bahnsen emphasizes that TAG is not a single “trick” or isolated argument. Its power emerges from its systematic, integrated approach. By tracing reasoning, logic, morality, and science back to their ultimate grounding in Christ, the series demonstrates that every fact, every law, and every operational principle of thought presupposes God. This Epilogue underscores that true comprehension requires listening, thinking, and reflecting across the entirety of the lectures. It is only through sustained engagement that the presuppositional approach becomes both clear and compelling, allowing the student to see how every precondition of knowledge finds its fulfillment in Christ.

TAG is not a soundbite. It is a sustained confrontation

with every claim, every fact, and every way we know reality.

All of it already points to God.

This Epilogue also serves as a reminder that apologetics is an active discipline. Understanding the preconditions of intelligibility is not merely an academic exercise; it is a formative practice that shapes how one approaches conversation, scholarship, and faith. The lectures invite students to wrestle with ideas, challenge assumptions, and internalize the Christian worldview as the coherent framework for all thought. By committing to the full series, the listener gains not only knowledge but the ability to apply the transcendental argument with integrity and clarity.

Bahnsen’s closing exhortation is both encouraging and urgent: TAG is not fully grasped in a single session or summary. The full lecture series provides the depth, historical grounding, and narrative cohesion necessary for the argument to exert its full force. Engaging the entire series is the pathway to seeing Christianity as the unavoidable foundation of reason, morality, and science — not just as a belief system, but as the very condition of intelligible thought.

LISTEN TO THE SERIES HERE:

- Four Types of Proof (1 of 10)

- Van Til’s Why I Believe in God (2 of 10)

- Kant in Context (3 of 10)

- Contemporary Transcendental Arguments, Part 1 (4 of 10)

- Contemporary Transcendental Arguments, Part 2 (5 of 10)

- Summary of Transcendental Arguments, Part 1 (6 of 10)

- Summary of Transcendental Arguments, Part 2 (7 of 10)

- Apologetical Transcendental Argument (8 of 10)

- Back to Basics (9 of 10)

- Van Til’s Critics: Hoover, Dooyeweerd, Frame (10 of 10)